What is Candida albicans and what causes an overgrowth?

Candida albicans is one of a variety of Candida species of yeasts which are found naturally in the human digestive and genitourinary tracts, mouth and skin 1, 2 and is one of the only types of fungal organism to cause disease in humans.2 When confined to specific sites within the body, in limited numbers and in a non-pathogenic (non-harmful) form, Candida albicans can thrive and presents no problems to its host. However, if the yeast establishes itself in other parts of the body, or alters its structure to become a more harmful fungal form, the human body launches an immune response in an attempt to attack and destroy the yeast cells. Certain factors which disrupt the natural balance of bacteria in the digestive or genitourinary tracts may lead to an immune response to Candida, triggering production of anti-Candida antibodies. Overgrowth of Candida can be caused by regular use of antibiotics, oral contraceptives or corticosteroids; stress; infection; high sugar and starch diets; and chlorinated water – essentially anything which suppresses the immune system or inhibits the growth of beneficial gut bacteria, both of which usually maintain Candida albicans at manageable levels. 1,3

How can Candida albicans be harmful?

‘Candida albicans is naturally present in both men and women and an overgrowth can lead to health issues of varying degrees of severity.’

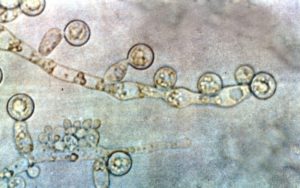

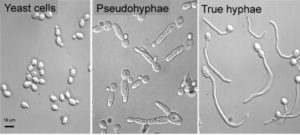

When the immune system is compromised and particularly after antibiotic use, when levels of beneficial bacteria are diminished, Candida cells can proliferate rapidly and may also change from a yeast form to a fungal form, developing hyphae, or threadlike filaments which help them to adhere to the lining of the gut. 1, 4 If the gut lining is also compromised, the hyphal form of Candida albicans is able to penetrate through this important defence barrier and enter the bloodstream.4 From here, Candida albicans is able to further disrupt the immune system by disintegrating the membrane (outer layer) of certain immune cells.5 The yeast cells release toxic by-products, which can be linked to a wide variety of symptoms including headaches, sinus infection, fatigue, poor concentration, aching joints, thrush, rectal itching, decreased libido, skin complaints such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis and commonly, a feeling described as ‘brain fog.’ These symptoms are so broad ranging and can easily be attributed to many other health issues, meaning that Candida overgrowth is often overlooked, unless it progresses to the extremely serious condition of invasive Candidiasis, which is a fungal infection of the blood, most often associated with severely immunocompromised and hospitalised patients and which can result in death.3

While the typical symptoms described above are obviously not life threatening, they can reduce quality of life and ongoing damage by Candida albicans hyphae (the fungal form) to the cells lining the digestive tract can lead to any number of other health issues. It is therefore important to identify and treat a yeast overgrowth, while also considering any other factors which may be contributing to the imbalance of microorganisms in the gut, for example a hormonal imbalance, including pancreatic, thyroid and sex hormones. Many pregnant women, or those taking the contraceptive pill or HRT find that they are more prone to vaginal or oral Candida infections,6 characterised by white spots on the infected skin cells,7 which is what people often associate with Candida. However, it is important to note that Candida albicans is naturally present in both men and women and an overgrowth can lead to health issues of varying degrees of severity, including localised mucosal infections within the mouth and genitourinary tract; widespread damage to the gastrointestinal system; or systemic invasion which affects the entire body, with the most severe form being a potentially fatal blood infection.7

How do I find out if I have a Candida overgrowth and what can I do about it?

‘The most important approach to treating Candida overgrowth is to boost the immune system…’

There are a few options for testing levels of Candida yeasts. A blood test can check for the presence of anti-Candida antibodies, indicating both past and current overgrowth; a stool test is useful for showing levels of Candida present in the colon; and a urine organic acids analysis can detect compounds released by Candida yeasts, which are not normally produced by human cells.

The most important approach to treating Candida overgrowth is to boost the immune system: replenishing the beneficial bacteria which usually keep the yeast in check; addressing anything else which could be causing inflammation to the gut lining, such as poor digestion, food intolerances, alcohol or smoking; eating a diet rich in immune supportive nutrients, which enable immune cells to function optimally in their attempt to attack and destroy excessive yeast cells; and managing lifestyle factors which impact on the immune system, such as stress, sleep and chemical exposure.

Various diets are used to try to manage yeast overgrowth, of which the Candida diet is well known and involves the avoidance of sugar, fruit, starchy vegetables, grains, most dairy products, fermented foods, certain nuts, vinegar and processed meats. I have seen mixed results with this approach, with some clients finding that severe and long-term restriction of carbohydrates reduces symptoms significantly, only for them to reoccur as soon as they re-introduce any kind of simple sugar into their diet. If this approach is to be followed, it is essential to re-establish beneficial gut bacteria effectively; to use natural anti-fungal agents such as garlic and oregano oil carefully; and to support the repair of the gut lining with specific nutrients. An alternative approach is to follow a low FODMAP diet, something often recommended to people experiencing digestive issues such as IBS. FODMAP is an acronym used to describe specific short chain carbohydrates and sugar alcohols that are often poorly digested and subsequently fermented by bacteria in the colon, leading to the production of gas, bloating and pain associated with various digestive issues. A low FODMAP diet excludes a variety of foods, including certain fruit and vegetables, grains and dairy products. Once again, replenishing beneficial gut bacteria, supporting the immune system and repairing the gut lining are vital parts of this process, with the aim of restoring balance within our delicate internal ecosystem, rather than trying to completely eliminate yeasts from the body. In this way, the presence of naturally occurring Candida albicans in its yeast form does not need to be a threat to healthy individuals.

View List of References

-

- Corouge M, Loridant S, Fradin C, Salleron J, Damiens S, Moragues M D, Souplet V, Jouault T, Robert R, Dubucquoi S, Sendid B, Colombel J F, Poulain D (2015) Humoral Immunity Links Candida albicans Infection and Celiac Disease. PLoS One, 10 (3) e0121776. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

- Nobile C J, Johnson A D (2015) Candida albicans Biofilms and Human Disease. Annual Review of Microbiology, 69: 71-92. [Online] Annual Reviews (http://www.annualreviews.org/).

- Pfaller M A, Diekema (2007) Epidemiology of Invasive Candidiasis: a Persistent Public Health Problem. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 20 (1):133-163. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

- Lu Y L, Su C, Liu H (2012) Candida albicans hyphal initiation and elongation. Trends in Microbiology, 22 (12): 707-714. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

- Thompson D S, Carlisle P L, Kadosh D (2011) Coevolution of Morphology and Virulence in Candida Species. Eukaryotic Cell, 10 (9): 1173-1182. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

- Paul L. Fidel, Jr., Jessica Cutright, and Chad Steele (2007) Effects of Reproductive Hormones on Experimental Vaginal Candidiasis. Infection and Immunity, 68 (2): 651-657. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

- Anaul Kabir M, Asif Hussain M, Ahmad Z (2012) Candida albicans: A Model Organism for Studying Fungal Pathogens. ISRN Microbiology, 538694. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).