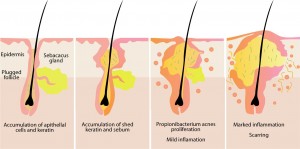

Acne vulgaris is an inflammatory skin disease which is most often associated with the onset of puberty, 1 affecting around 85% of teenagers. 2 However, it has become increasingly common in the past 50 years, notably among adult women. 3 The precise mechanisms of acne development are still not fully understood, but it is characterised by overproduction of sebum (the oily secretion produced by sebaceous glands in the outer layer of skin); disruption of the cells which line hair follicles; and inflammation; in conjunction with hormonal and bacterial influences. 4,3,5

Recent studies have focused on the role that insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) plays in acne. IGF-1 is a hormone which promotes cell growth and is naturally higher during puberty. 6 Elevated levels of IGF-1 lead to increased sebum production and over-production of the cells which surround sebaceous follicles, 4 with subsequent clogging of pores. Bacteria such as Propionibacterium acnes, which is normally present in the skin, may become trapped in clogged pores, leading to infection and the redness and swelling of acne lesions.1 Consumption of cow’s milk results in a significant increase in blood levels of IGF-1, 7 while epidemiological studies show that acne is absent in populations consuming paleolithic diets, with low glycaemic load and no consumption of milk or dairy products. 6,8 Whey protein extracts are of particular concern, with various studies focusing purely on acne development in users of whey protein supplements. 9,18 Whey protein extract from cow’s milk contains 6 different growth factors, hence its use for increasing muscle mass, but which could also be the reason why whey protein supplementation is linked to the onset of acne. 18

”epidemiological studies show that acne is absent in populations consuming paleolithic diets, with low glycaemic load and no consumption of milk or dairy products.”

Acne has been referred to as ‘diabetes of the skin’ by scientists since the 1950s. 3 Insulin is necessary for the body to convert glucose into energy, but excess insulin in the bloodstream can cause an increase in IGF-1, 6 which in turn promotes skin cell growth. Increased insulin also raises levels of androgens (male hormones, including testosterone, which women usually produce in lesser amounts).10 Androgens are implicated in increased sebum production and excessive skin cell turnover,1,11 both of which can trigger acne. Diet plays a vital role, as high glycaemic foods such as sugar, white bread, white potatoes and white rice cause insulin levels to rise, but may also affect other cell proteins such as mTORC1 and Fox01 proteins, which regulate cell growth, sebum production, insulin sensitivity and hormone activity: 6 all factors implicated in the development of acne. A low carbohydrate diet is recommended, 12 avoiding any refined or processed foods and limiting dairy, while focusing on good quality protein, essential fats and anti-oxidant rich vegetables.

An important dietary factor that influences inflammation, is the relative intake of omega 6 to omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in food. Omega 3 fats reduce the production of inflammatory signalling molecules in sebaceous glands; 4,10 inhibit mTORC1 (a protein which can signal sebaceous glands to produce more sebum); 4 may help to maintain IGF-1 levels (thus preventing over-production of skin cells); and are also antibacterial, inhibiting the growth of Propionibacterium acnes and Staphylococcus species of bacteria which are involved in acne. 13 Modern diets tend to be higher in omega 6 fats (from vegetable oils used in processed foods), as well as saturated fats and trans fats, all of which can be converted to inflammatory substances called prostaglandins, while omega 3 fats have an anti-inflammatory effect on the body. 4,10 Observational studies have noted low occurrence of acne in populations who eat high amounts of omega 3-rich oily fish such as salmon, mackerel, herring, fresh tuna and anchovies. 14

”If the liver is overburdened, the lungs or skin may be used as an alternative route to remove toxins, so skin problems are often an indication that the liver needs supporting.”

Various nutrients have been found to be low in patients with acne, including chromium, selenium, vitamins A and E, and zinc. 5,15,16 In women with polycystic ovarian syndrome, acne was decreased following supplementation with chromium 15 and selenium. 16 Chromium is found in wholegrains, brown rice, eggs, meat, fish, mushrooms and Brewer’s yeast and has been shown to help balance blood sugar levels, while selenium is an important antioxidant found in Brazil nuts, fish, seafood, poultry, brown rice and mushrooms. Vitamin A (found in oily fish, eggs and liver) and the vitamin A pre-cursor, beta carotene (found in dark green, yellow and orange vegetables) help cells to function and reproduce normally, replacing themselves roughly every month. 17 Vitamin E (found in soya, avocado, olive oil, nuts and seeds) helps to maintain hormone balance, is an important antioxidant nutrient and also helps to prevent scarring from acne. The acne fighting properties of zinc (found in oysters, oats, meat, poultry, nuts and beans) are believed to be due to its ability to reduce inflammation and to kill bacteria, as well as its involvement in hormone production and androgen regulation. 1, 5 Green tea has been used topically in studies and found to be effective in improving mild to moderate acne, which is attributed to the antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties of its flavonoids and tannins. 2,4

Two crucial factors, which are often overlooked in skin health, are the liver and digestive tract. The liver fulfils over 400 functions in the body, of which detoxification is one of the most important. All toxins which are produced by or enter the body are managed by the liver, which eliminates them via various processes. If the liver is overburdened, the lungs or skin may be used as an alternative route to remove toxins, so skin problems are often an indication that the liver needs supporting. Cutting back on sugar, alcohol and processed foods is beneficial, as well as increasing water intake and consuming a wide variety of vegetables which contain vital nutrients required for detoxification processes.

Two crucial factors, which are often overlooked in skin health, are the liver and digestive tract. The liver fulfils over 400 functions in the body, of which detoxification is one of the most important. All toxins which are produced by or enter the body are managed by the liver, which eliminates them via various processes. If the liver is overburdened, the lungs or skin may be used as an alternative route to remove toxins, so skin problems are often an indication that the liver needs supporting. Cutting back on sugar, alcohol and processed foods is beneficial, as well as increasing water intake and consuming a wide variety of vegetables which contain vital nutrients required for detoxification processes.

An imbalance of bacteria in the gut, or digestive issues such as constipation can also put pressure on the liver, with subsequent impact on skin health. Bacteria and yeasts may release toxins in the digestive tract, leading to intestinal inflammation, 19 which in turn puts pressure on the liver. Inflammation can also promote insulin resistance in cells that control blood glucose, 20 which brings us back to the link between elevated insulin; over production of skin cells and androgens; and acne. Overall, an anti-inflammatory diet is recommended to address the underlying causes of acne, with many studies concluding that a paleolithic diet is the best approach. It is advisable to investigate any potential digestive dysfunction and to support liver health, while consuming plenty of unrefined, wholefoods and essential fats, including oily fish, nuts and seeds, as well as a wide variety of fruit and vegetables, focusing on sources of vitamin A, vitamin E, chromium, selenium and zinc.

Overall, an anti-inflammatory diet is recommended to address the underlying causes of acne, with many studies concluding that a paleolithic diet is the best approach. It is advisable to investigate any potential digestive dysfunction and to support liver health, while consuming plenty of unrefined, wholefoods and essential fats, including oily fish, nuts and seeds, as well as a wide variety of fruit and vegetables, focusing on sources of vitamin A, vitamin E, chromium, selenium and zinc.

View List of References

- Pizzorno J E, Murray M T, Joiner-Bey H (2008) The Clinicians Handbook of Natural Medicine, 2nd Churchill Livingstone, USA.

- Nasri H, Bahmani M, Shahinfard N, Moradi Nafchi A, Saberianpour S, Rafieian Kopaei M (2015) Medicinal Plants for the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris: A Review of Recent Evidences. Jundishapur Journal of Microbiology, 8(11): e25580. [Online] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Rubin M G, Kim K, Logan A C (2008) Acne vulgaris, mental health and omega-3 fatty acids: a report of cases. Lipids in Health and Disease, 7: 36. [Online] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Melnik B C (2015) Linking diet to acne metabolomics, inflammation, and comedogenesis: an update. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology, 8: 371-388. [Online] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Mogaddam M R, Ardabilj N S, Maleki N, Soflaee M (2015) Correlation between the Severity and Type of Acne Lesions with Serum Zinc Levels in Patients with Acne Vulgaris. Biomedical Research International. [Online- Epub ahead of print] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Melnik B C, Zouboulis C C (2013) Potential role of FoxO1 and mTORC1 in the pathogenesis of Western diet-induced acne. Journal of Experimental Dermatology, 22(5): 311-315. [Online] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Melnik B C, Schmitz G (2009) Role of insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1, hyperglycaemic food and milk consumption in the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris. Experimental Dermatology, 18(10): 833-841. [Online] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Melnik B C (2012) Diet in acne: further evidence for the role of nutrient signalling in acne pathogenesis. Acta-Dermato Venereologica, 92(3): 228-231. [Online- abstract only] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Melnik B C (2011) Evidence for acne-promoting effects of milk and other insulinotropic dairy products. Nestle Nutrition Workshop Series Pediatric Program, 67: 131-145. [Online] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Kaimal S, Thappa D M (2010) Diet in dermatology: Revisited. Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology, 76(2): 103-115. [Online] Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology (www.ijdvl.com).

- Imperato-McGinley J, Gautier T, Cai L Q, Yee B, Epstein J, Pochi P (1993) The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 76(2): 524-528. [Online- abstract only] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Kwon H H, Yoon J Y, Hong J S, Jung J Y, Park M S, Suh D H (2012) Clinical and histological effect of a low glycaemic load diet in treatment of acne vulgaris in Korean patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta-Dermato Venerelogica, 92(3): 241-246. [Online] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Desbois A P, Lawlor K C (2013) Antibacterial Activity of Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids against Propionibacterium acnes and Staphylococcus aureus. Marine Drugs, 11(11): 4544-4557. [Online] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Khayef G, Young J, Burns-Whitmore B, Spalding T (2012) Effects of fish oil supplementation on inflammatory acne. Lipids in Health and Disease, 11:165. [Online] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Jamilian M, Bahmani F, Siavashani M A, Mazloomi M, Asemi Z, Esmaillzadeh A (2015) The Effects of Chromium Supplementation on Endocrine Profiles, Biomarkers of Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Biological Trace Elements Research, Epub ahead of print. [Online- abstract only] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- B. Razavi M, Jamilian M, Kashan Z F, Heidar Z, Mohseni M, Ghandi Y, Bagherian T, Asemi Z (2015) Selenium Supplementation and the Effects on Reproductive Outcomes, Biomarkers of Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Hormone and Metabolic Research, Epub ahead of print. [Online- abstract only] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Beckenbach L, Baron J M, Merk H F, Loffler H, Amann P M (2015) Retinoid treatment of skin diseases. European Journal of Dermatology, 25(5): 384-391. [Online] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Carvalho Pontes T, Fernandes Filho G M C, de Sousa Pereira Trinidade A, Sobral Filho J F (2013). Incidence of acne vulgaris in young adult users of protein-calorie supplements in the city of João Pessoa–PB. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia, 88(6):907-912. [Online] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Reinoso Webb C, Koboziev I, Furr K L, Grisham M B (2016) Protective and pro-inflammatory roles of intestinal bacteria. Pathophysiology [Online- Epub ahead of print] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

- Cavallari J F, Denou E, Foley K P, Khan W I, Schertzer J D (2016) Different Th17 immunity in gut, liver, and adipose tissues during obesity: the role of diet, genetics, and microbes. Gut Microbes, 2(7): 82-89. [Online] PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).