Christmas parties have already started, with over-consumption of rich food and alcohol proving problematic for many. However, even a healthy diet can cause symptoms of indigestion, if stomach acid is depleted.

Did you know that as you age, your levels of stomach acid are likely to drop?1 You might not have given this much thought, but hydrochloric acid (HCl) has a number of vital roles in the body and an excess, or more commonly a deficiency, can severely impact your health. In fact, low stomach acid or hypochlorhydria, can be linked to a wide range of digestive and malabsorption issues from indigestion, osteoporosis and pernicious anaemia to acne rosacea, low energy and brittle nails.2-5

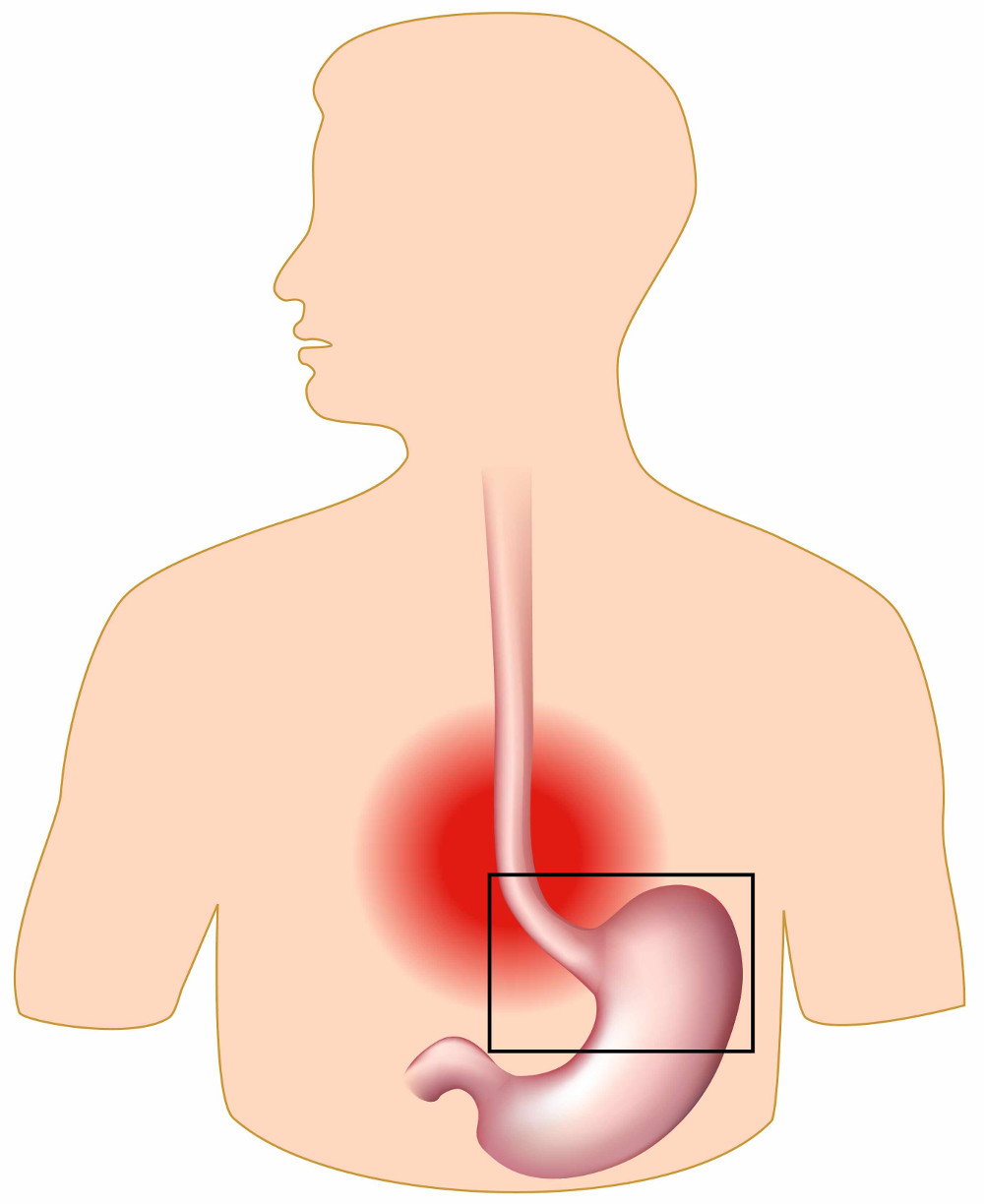

Indigestion is commonly attributed to excess levels of acid in the stomach, but more often than not, stomach acid is low and it is the poor digestion of food which can trigger acid reflux

HCl is involved in the digestion of food. It helps to break down protein in particular, which is essential for the growth, repair and renewal of all cells in the body. If we do not have enough stomach acid, partially digested food proteins can trigger a series of reactions, including the development of food intolerances and allergies.6 Carbohydrates are digested in the small intestine, but rely on the secretion of stomach acid to stimulate the pancreas to release digestive enzymes into the digestive tract. If stomach acid is low, the pH of the stomach becomes too high, pancreatic enzymes are not secreted7 and carbohydrates are not broken down completely. Fermentation of these carbohydrates by bacteria produces gas, which causes bloating, wind and stomach cramps.8

Indigestion is commonly attributed to excess levels of acid in the stomach, but more often than not, stomach acid is low and it is the poor digestion of food which can trigger acid reflux, also known as Gastro-oesophageal Reflex Disease (GERD), with symptoms such as heartburn and burping or bloating after meals. The risk of GERD increases with age,9 while stomach acid secretions decline, which adds weight to the argument that it is in fact inadequate stomach acid which is linked to the symptoms of reflux. Recent studies used MRI scanning to demonstrate that there is abnormal structure and function of the junction where the oesophagus meets the stomach in GERD patients.10,11 Gas from undigested carbohydrates produces pressure within the abdomen12 and could affect the valve mechanism designed to prevent reflux. Any amount of acid which flows back up into the oesophagus will cause pain and damage and it should not automatically be assumed that the escape of this acid is caused by excess amounts in the stomach.

…if HCl levels are low, you are unlikely to be absorbing optimum amounts of nutrients from food, regardless of how healthy your diet is.

Hydrochloric acid serves as a defence mechanism, killing potentially harmful bacteria that we ingest through food and water.13 If stomach acid is low, harmful bacteria may survive and Helicobacter pylori is a particular organism which becomes increasingly common as we age.14 It can cause inflammation of the stomach lining and is strongly associated with stomach ulcers and possibly cancer.15

Finally, stomach acid is necessary for the absorption of certain nutrients such as iron, calcium and zinc, plus vitamins C and vitamin B12. Therefore, if HCl levels are low, you are unlikely to be absorbing optimum amounts of nutrients from food, regardless of how healthy your diet is. Poor absorption of vitamins and minerals has negative implications for the health of our bones, muscles, nerves and immune system, amongst many other body functions.

So how can you check your levels of stomach acid? An easy test which you can take at home will give a rough indication of acidity. Mix ½ teaspoon of bicarbonate of soda with 60ml water and drink on an empty stomach (e.g. first thing in the morning, before any food or drink). If sufficient acid is present, it will react with the alkaline bicarbonate of soda, producing gas (i.e. lots of burping). If you do not burp over the next 10-15 minutes, it may be an indication that stomach acid is low.

There are a few ways to increase stomach acid, while encouraging your stomach to boost its own natural production. You can drink apple cider vinegar before meals, adding 1 teaspoon of vinegar to water and gradually increasing over a week to up to 10 teaspoons with each meal. If you experience a burning sensation, drink some bicarbonate of soda mixed with water to neutralize the acidity.

It is important to chew your food properly in order to stimulate the digestive process; to eat small meals more frequently; and to avoid drinking too much liquid with meals, as fluids dilute stomach acid. It is advisable to take a quality multi vitamin and mineral supplement, including adequate levels of zinc (critical for the production of stomach acid) and an alternative to drinking apple cider vinegar is to take a supplement of betaine hydrochloride,16 although it is advisable to first seek professional nutrition advice.

View List of References

1. Krasinski S D, Russell R M, Samloff I M, Jacob R A, Dallal G E, McGandy R B, Hartz S C (1986) Fundic atrophic gastritis in an elderly population. Effect on hemoglobin and several serum nutritional indicators. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 34: 800-806. [Online – Abstract only] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

2. Sharp G S, Fister H W (1967) The diagnosis and treatment of achlorhydria: ten year study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 15 (8). [Online] Wiley Online Library (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com).

3. Insogna K L (2009) The effect of proton pump-inhibiting drugs on mineral metabolism. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 104: S2-4. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

4. Merriman N A, Putt M E, Metz D C, Yang Y X (2009) Hip Fracture Risk in Patients with a Diagnosis of Pernicious Anemia. Gastroenterology, 138: 1330-1337. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

5. Epstein N, Susnow D (1931) Acne Rosacea with particular reference to gastric secretion. Western Journal of Medicine, 35: 118-120. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

6. Moron B, Bethune M T, Comino I, Manyani H, Ferragud M, Carlos Lopez M, Cebolla A, Khosla, Sousa C (2008) Toward the Assessment of Food Toxicity for Celiac Patients: Characterization of Monoclonal Antibodies to a Main Immunogenic Gluten Peptide. PLos One, 3: e2294. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

7. Wang J, Barbuskaite D, Tozzi M, Giannuzzo A, Sorensen C E, Novak I (2015) Proton Pump Inhibitors Inhibit Pancreatic Secretion: Role of Gastric and Non-Gastric H+/K+-ATPases. PLOS One, 10: e0126432. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

8. Fernández-Bañares F, Rosinach M, Esteve M, Forné M, Espinós JC, Maria Viver J (2006) Sugar malabsorption in functional abdominal bloating: a pilot study on the long-term effect of dietary treatment. Clinical Nutrition, 25: 824-831. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

9. Greenwald D A (2004) Aging, the gastrointestinal tract, and risk of acid-related disease. The American Journal of Medicine, 117: 8-13. . [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

10. Curcic J, Roy S, Schwizer A, Kaufman E, Forras-Kaufman Z, Menne D, Hebbard GS, Treier R, Boesiger P, Steingoetter A, Fried M, Schwizer W, Pal A, Fox M (2014) Abnormal structure and function of the esophagogastric junction and proximal stomach in gastroesophageal reflux disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 109: 658-667. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

11. Steingoetter A, Sauter M, Curcic J, Liu D, Menne D, Fried M, Fox M, Schwizer W (2015) Volume, distribution and acidity of gastric secretion on and off proton pump inhibitor treatment: a randomized double-blind controlled study in patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) and healthy subjects. BMC Gastroenterology, 15: 111. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

12. Robayo-Torres C C, Quezada-Calvillo R, Nichols B L (2006) Disaccharide digestion: clinical and molecular aspects. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 4: 276-287. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

13. Sarker S A, Gyr K (1992) Non-immunological defence mechanisms of the gut. Gut, 33: 987-993. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

14. Remond D, Shahar D R, Gille D, Pinto P, Kachal J, Peyron M A, Nunes Dos Santos C,Walther B, Bordoni A, Dupont D, Tomas-Cobos L, Vergeres G (2015) Understanding the gastrointestinal tract of the elderly to develop dietary solutions that prevent malnutrition. Oncotarget, 6: 13858-13898. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).

15. Kuiper E J (2006) Proton Pump Inhibitors and Helicobacter pylori Gastritis: Friends or Foes? Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology, 99: 187-194. [Online] Wiley Online Library (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com).

16. Yago M R, Frymoyer A, Benet L Z, Smelick G S, Frassetto L A, Ding X, Dean B, Salphati L, Budha N, Jin J Y, Dresser M J, Ware J A (2014) The Use of Betaine HCl to Enhance Dasatinib Absorption in Healthy Volunteers with Rabeprazole-Induced Hypochlorhydria. The AAPS Journal, 16: 1358-1365. [Online] PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc).